How many exoplanets are there? No one knows the answer, but surely, with the James Webb Space Telescope fully operational, it's only a matter of time before we start finding new exoplanets in the far reaches of space. One example is the recent discovery of a new star system called Trappist-1.

Trappist-1's star is an ultracold red dwarf with a surface temperature of just 2,500 degrees Celsius, which is pretty cool for stars, compared to our sun's 5,800 degrees Celsius. Even in terms of size, it's only 9 percent as massive as the sun. The star system is about 40 light years from Earth, so it's currently out of reach for humans, who, of course, lack the technology to make it happen.

In the Trappist-1 system, scientists found three exoplanets orbiting the star, which was discovered by an observatory in Chile. In addition, the three planets orbiting the star are named TRAPPIST-1B, TRAPPIST-1C and TRAPPIST-1D. After months of studying the system, astronomers have concluded that 1B and 1C have no gaseous atmospheres, meaning they are rocky worlds, similar to Earth. In the future, once we achieve interstellar travel, these two planets could be candidates 39bet-đua chó-game giải trí -đá gà-đá gà trực tuyến-đánh bài.

Crucially, scientists believe they lack a suffocating hydrogen-helium envelope that would increase the chances of habitability. Not only that, scientists have found four more planets orbiting the star. This is interesting because our solar system has eight planets orbiting the Sun. But apart from this similarity, the two star systems have no other similarities and look very different from each other.

That's because all seven planets orbiting Trappist 1 are the same size as Earth. Moreover, some of them are in habitable zones. This region is close enough to the star, but also far enough away, where planets can easily sustain liquid water, which is important because liquid water happens to be a key ingredient for life. All of these planets were discovered thanks to NASA's Spitzer Telescope and other ground-based observatories.

While the Spitzer mission was still conducting scientific research, it observed the system for more than 1,000 hours. Even the Kepler telescope is getting involved with the system. Regrettably, however, both missions have now been decommissioned. So for now, the Ames Webb Space Telescope will continue their research and provide us with even more valuable information. It is believed that each of the seven planets will be studied by Webb.

As we mentioned earlier, the planets in Trappist-1 are different from those in our solar system. For one thing, all Trappist planets orbit very close to their stars. In fact, they're so close that if we combine their orbits, they're about the same as Mercury's orbit. Trappist-1b, for example, takes just 1.5 days to orbit its star, but has the same size and mass as Earth. Not only that, but is it a coincidence that all the TRAPPIST-1 planets look rocky and similar to Earth in terms of mass and size?

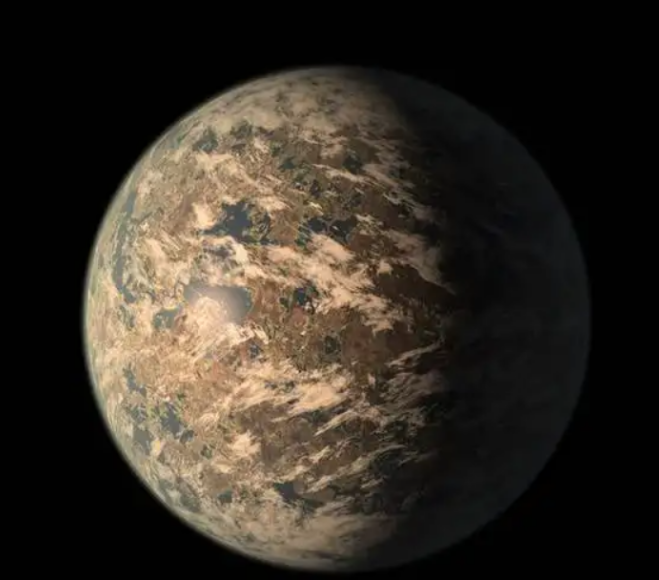

And even then, sadly, they're not necessarily habitable. Some are too hot, some are too cold. Although by combining direct observations with computer-generated models, scientists believe their density is similar to that of our planet. But again, we can't tell if they're barren and gray, like the moon, or wet and green, like the Earth. Density, while an important clue to a planet's composition, doesn't tell us anything about its habitability. Not only are they all rocky planets, but some of them apparently have liquid water, too. Still, it's not clear whether this water will exist in liquid form, like water on Earth. These similarities make the TRAPPIST-1 system one of the most important galaxies for scientists to study, because it's so similar to our own star system!

And even then, sadly, they're not necessarily habitable. Some are too hot, some are too cold. Although by combining direct observations with computer-generated models, scientists believe their density is similar to that of our planet. But again, we can't tell if they're barren and gray, like the moon, or wet and green, like the Earth. Density, while an important clue to a planet's composition, doesn't tell us anything about its habitability. Not only are they all rocky planets, but some of them apparently have liquid water, too. Still, it's not clear whether this water will exist in liquid form, like water on Earth. These similarities make the TRAPPIST-1 system one of the most important galaxies for scientists to study, because it's so similar to our own star system!

With luck, it might even help us answer the greatest scientific and philosophical question of all time: Are we alone? We know that every planet in our solar system plays a very important role, and there are a lot of planets out there that are very different from our planet. Which raises the question, how did our solar system come into being? Perhaps the James Webb Space Telescope will answer these questions soon, now that it has released its first extrasolar images to the world.

According to the Webb team, JWST will spend a quarter of its lifetime studying exoplanets, and 8.2 percent of that time will be spent looking at the Trappist-1 system. A major theme of the JWST observations is atmospheric reconnaissance to see if there is an atmosphere around Trappist-1. Scientists have tried to probe the atmosphere using the Hubble Space Telescope, but have failed to find any solids. To sum up, the JWST is designed to detect what Hubble will never be able to detect! If an atmosphere is found around a TRAPPIST-1 planet, it will be extremely important for the study of exoplanets.

Some scientists have hypothesized that the system's stellar flares may have disrupted the atmospheres of rocky planets that are so close to their host stars that they could easily cause tidal locking. Tidal locking, a gravitational mechanism that affects near-Earth planets and keeps one hemisphere of the planet facing the star at all times, could significantly alter the characteristics of these atmospheres. Depending on the presence of oceans, plate tectonics, and even life, geological and biological processes can recycle carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen through the atmospheres of rocky planets to produce various components. But in order to study these questions, a sample must first be found. And this star system could be the key to unlocking the possibility of exoplanet habitability!